Fallen & Forgotten: Why were these missing WWII heroes buried under pavement?

Howard Brisbane's relatives thought he was buried in an idyllic setting. But only days after his death, the WWII servicemember's gravesite was gone – turned into a parking lot, first paved by Americans.

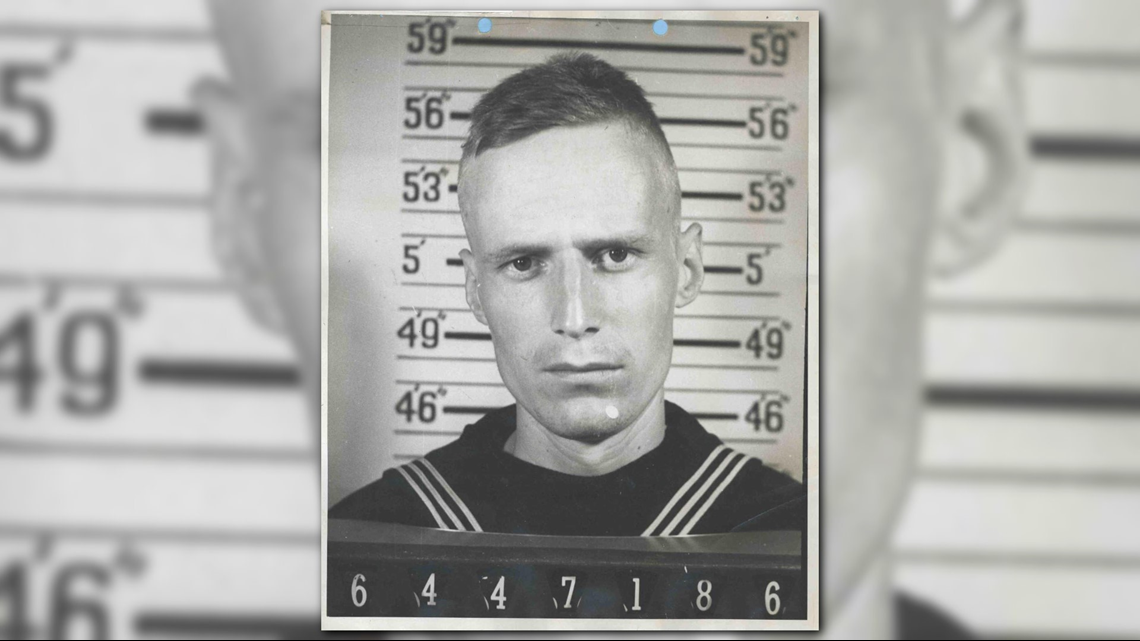

United States Navy

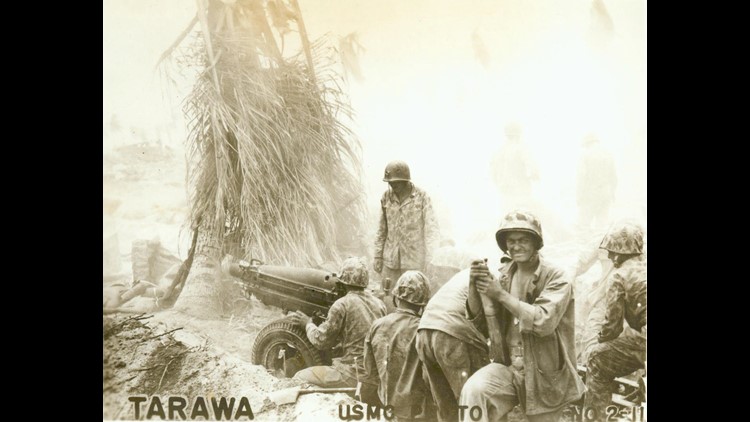

TARAWA, REPUBLIC OF KIRIBATI (WUSA9) — He lay in repose under the ravages of war. A United States Navy sailor remained in a mass grave for 70 years, forgotten, far from the fields of Arlington National Cemetery.

A green poncho clung to his battered bones, as he rested near fallen Marines as young as 17. The men defeated the Japanese on a sandbar later known as, “one square mile of hell.”

They died before Thanksgiving 1943, more than a year before the world would see the iconic flag over Iwo Jima.

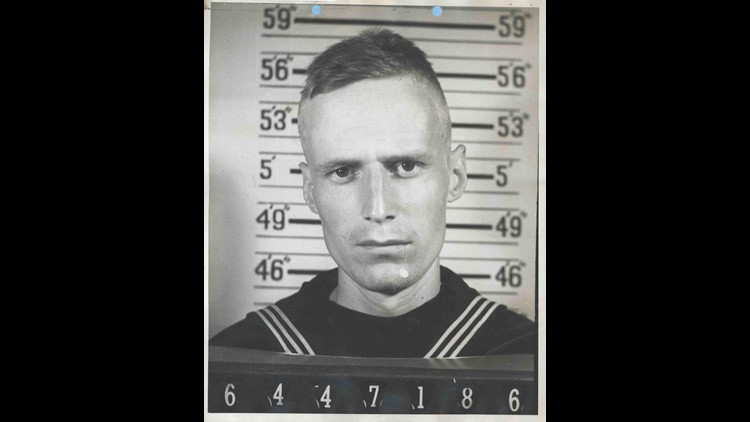

The body of Howard P. Brisbane lay underneath the sands of Tarawa, a remote Pacific atoll more than 7,000 miles from Arlington. Brisbane was 21 years old, a Navy medic destined to save U.S. Marines on the faraway beaches.

PHOTOS: American WWII heroes forgotten in Pacific graves

He waded through water on the first day of fighting, as battalions’ boats came under relentless Japanese fire.

In Defense Department photographs never released to the public, what caused his end is clear – a single sniper’s bullet to the head. The image confirms stories from his family since the telegram came before Christmas, nearly 74 years ago.

But Brisbane’s living relatives, including a niece who remembers the telegram at her front door, always thought he was buried in an idyllic setting – a paradise saved from the Japanese Navy.

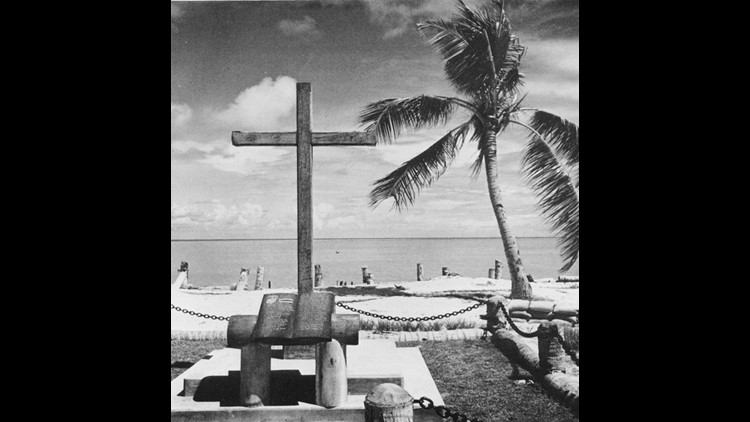

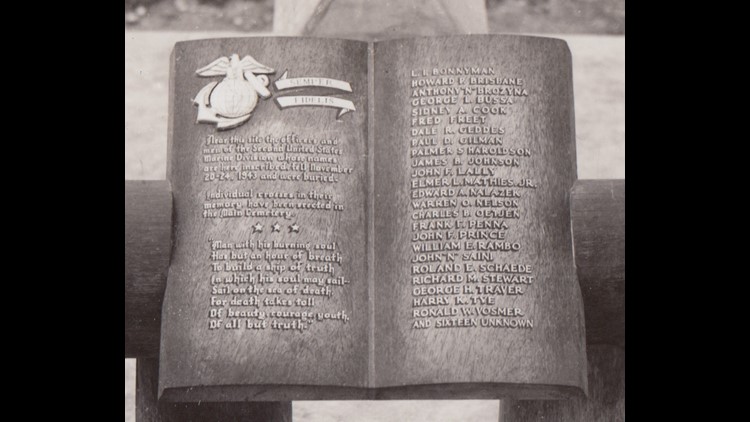

They saw black and white photographs showing landscapes rivaling the poignant beauty of Normandy. White crosses near white beaches, palm trees and a plaque, forever commemorating the sacrifices of men who marched with the Second United States Marine Division.

But only days after his death, Brisbane’s gravesite was gone.

There was no cross in the ground above his body.

There was dust.

His cemetery became a gravel road and parking lot by the spring of 1944, first paved by Americans.

After the Battle of Tarawa ended, the survivors dug trenches. They placed the dead side-by-side, burying them quickly. There was no time to fly men back to Arlington. A war needed to be won.

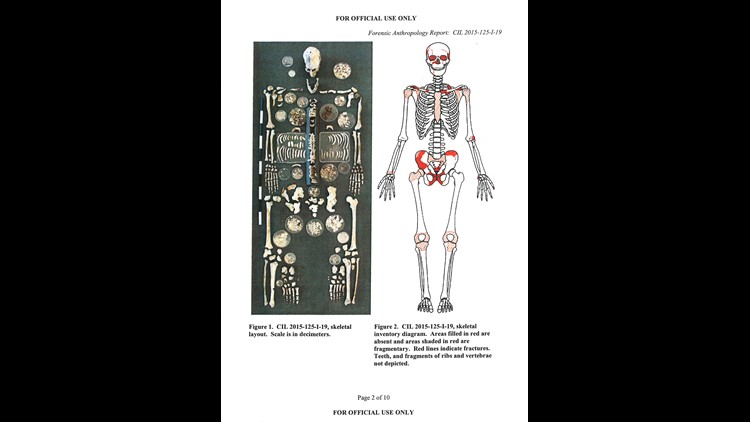

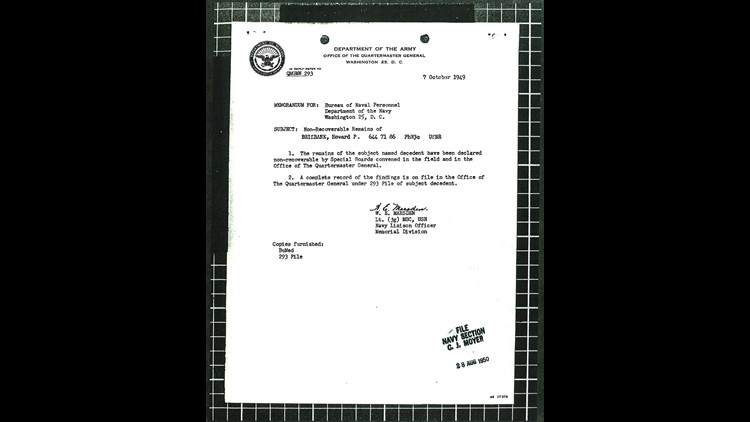

Government documents show Brisbane’s grave was forgotten for decades, his remains declared “non-recoverable” by a defense review board in 1949. But his skeleton, possessions, even the leather boots on his feet, were still there.

In a WUSA9 investigation extending seven months, interviews and records show the new government agency in charge of recovering America’s war dead never informed the Brisbane Family of the full circumstances surrounding his resting place on Tarawa.

Defense Department liaisons to the family never mentioned that a private citizen used his own money to first find Brisbane’s body, rather than D.O.D. teams leading the effort.

NOTE: Click through the above timeline for dates on the Battle of Tarawa and the Brisbane Family's journey to the truth

Interviews with the U.S. Government Accountability Office reveal the arm of the Pentagon tasked with finding lost graves still lacks personnel files for thousands of service members who are missing in action.

Data from the Pentagon show an annual goal of identifying the remains of 200 Americans was only met for the first time, one month ago. The findings from the new information requests have not been previously reported.

Defense personnel identified the remains of 201 troops this year, exceeding the goal by one service member.

Brisbane was one of nearly 73,000 Americans who are still missing from World War II. The staggering number of men who never returned is the rough equivalent of one in five graves missing from Arlington National Cemetery.

Both successes and long-standing inefficiencies colored the Navy corpsman’s return to Arlington in 2017, when his family saw his final burial among the dignified rows of marble graves. His homecoming was delayed for decades, with hundreds of men on Tarawa still below the surface of the sand.

Brisbane’s re-internment in American soil is one of the latest cases to shed light on a promise still in progress – the effort to bring thousands back to America in the face of uncertain funding and fading memories.

Uncle Howard

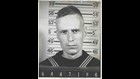

He joined the Navy seven months after Pearl Harbor, eventually becoming a medic who fought alongside the Marines. Howard Pascal Brisbane was from Birmingham, Ala., moving with his family to the charming homes of Arabella Street in New Orleans by the 1940’s, the neighborhood where his family lives to this day.

“Some of my earliest memories have Howard in them,” recalled Judy Landry, Brisbane’s niece who joined her brothers John and Byron for a June interview. “He was an identical twin, and I knew he and his brother would always play tricks on girls. One would make a date and the other would show up instead.”

Brisbane had deep brown eyes, and dreamed of becoming an artist. Drawings lined the walls of his home, and when he took a break, he brought Judy down the sun-splashed streets near the banks of the Mississippi – walks with just the two of them through the park.

Months later, Landry experienced a moment she was too young to understand – it was war at Christmastime when the telegram came.

“I answered the door, and my mother came, got the telegram, and started crying, very emotional,” Landry said. “And then, they made me keep it a secret until after Christmas. I mean, I was four. Keep it a secret from my grandfather so he wouldn’t be upset.”

She would later see a picture from the Pacific, with a white cross that said “Brisbane.” The photo was one of the family mementos lost in Hurricane Katrina, along with other priceless photographs of Howard.

“I remember one time, somebody said, maybe we could bring him home. And my grandfather said, ‘no he died once and that’s the end of it,’” Landry said. “But it wasn’t anything official. So that was the end of it. Never knew he was missing.”

One square mile of hell

It takes 20 hours today to fly from Washington, D.C. to Tarawa – a group of secluded coral islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

The island of Betio is the largest landmass within the Tarawa atoll, a sandbar the size of the National Mall.

It was on this remote outpost in 1941 where a massacre set the tone for the bloodshed and military might tied to Tarawa.

The Japanese beheaded 17 unarmed Allied intelligence operatives on Betio, along with five civilians. Their bodies were burned, and the island quickly transformed into a military fortress.

The operation to capture Tarawa called for grit, American’s first offensive in the critical Central Pacific. The impending invasion required an intrepid force with minimal margin for error. But a mistake marred the American assault from the early morning hours of Nov. 20, 1943, a mistake that likely cost Brisbane his life.

The tides of Tarawa are notoriously unpredictable, with dozens of ghost ships ravaged along its reefs to the present day. Battered boats from 1943 also remain, along with rusted armored tanks still submerged in the shallow lagoon.

RELATED: 8 facts you didn't know about Tarawa

Most amphibious vehicles cleared the reefs, but boats became stuck on the coral coming out of the choppy waters. There was no choice but for the Marines and Navy sailors to abandon their boats and wade ashore.

They waded the distance of up to 10 football fields, all while coming under intense machine gun fire.

Snipers in trees and concrete bunkers picked off Americans, including the medical personnel there to keep the wounded Allies and Japanese alive – medics like Brisbane.

“Death occurred immediately,” notes a postmortem military medical record. “Killed during the assault on Beach Red 3 sometime during the first day of the battle.”

PHOTOS: Tarawa past and present

PHOTOS: Tarawa past and present

Brisbane was 21 years old, his birthday only a month away, on the day after Christmas.

Men of the battalions began calling the island “one square mile of hell,” with more than 3,600 Japanese Marines fighting to the death. The number of Japanese who survived, 17, could be loaded into a school bus.

In all, 961 American servicemen were killed in the primary attack on Tarawa.

Today, 452 of them are still missing.

Losing the dead, under the sand

Archival footage shows blackened bodies washed ashore on the sands of Tarawa. Decomposition was quick, with scorching tropical temperatures and oppressive high humidity.

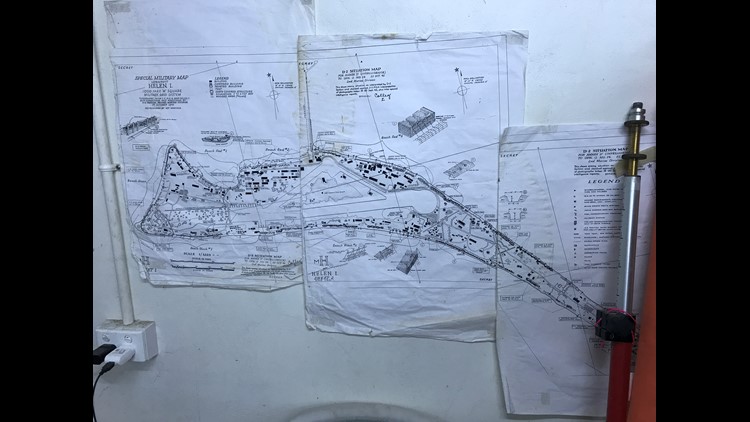

A Navy map from the National Archives shows Americans were buried in 41 separate sites, most of them laid in trenches. After three days of battle, landing troops were replaced by U.S. Navy construction battalions, known as "SeaBees," with little knowledge of burial locations.

The island’s airstrip needed to be lengthened for Allied B-24 bombers to land. Parking lots and cargo depots also needed to be constructed, in the same area where Howard was buried.

“These units engaged in construction projects requiring movement or re-arrangement of the known burials or grave markers,” reads a 2015 D.O.D. report prepared for the Brisbane Family.

Aerial photographs from 1944 show Howard’s grave was in the path of a new road connecting the airstrip to a pier. Crews constructed a road and a parking lot over Howard’s grave, placing a memorial for the dead away from the pavement.

NOTE: Slide middle bar left to right to see a comparison of Tarawa then and now

The memorial consisted of a bronze tablet and cross, but it had no bodies underneath. Americans were unable to find Howard’s remains for more than 70 years, because the memorial was 313 feet away from the actual remains of the fallen.

“Grave markers had been moved without any correspondence to the graves they were supposed to be marking,” the D.O.D. report said. “No records of the movements have been found, and we suspect none were kept.”

Additionally, a small white cross bearing Brisbane’s name was put in a cemetery clear across the other side of the runway. No remains of the Navy sailor were underneath.

The Pentagon never told the Brisbane Family that Americans paved over the sailor’s gravesite. The report does not clearly indicate the small cross belonging to Brisbane no longer exists, and his body was never underneath it – a fact that confounded and disillusioned his descendants 73 years later.

Documents not only failed to explain specifically why the bronze plaque was far from Brisbane’s real grave, but also failed to disclose the large memorial cannot be found today. The fate of Brisbane’s memorials remains unclear, a cross and plaque now lost to history.

He lay first under the ravages of war, then under American airplanes, then under rusting shipping containers. The Brisbanes lived on, comforted that Howard was at peace along the Pacific shores of an island they never knew.

The graves of Tarawa today

Only steps from pigpens, trash pits, and corroding cars, the Marines of Tarawa have sand cleaned from their skulls, excavations now in progress by private citizens.

The sight of a forgotten American in a pit, surrounded by poverty, draws a striking contrast with the sacred ground of Arlington. As anthropologists kneel four feet below the surface, exposed leg bones jut out from a pair of military-issued brown boots – heels pointed up, toes in the ground.

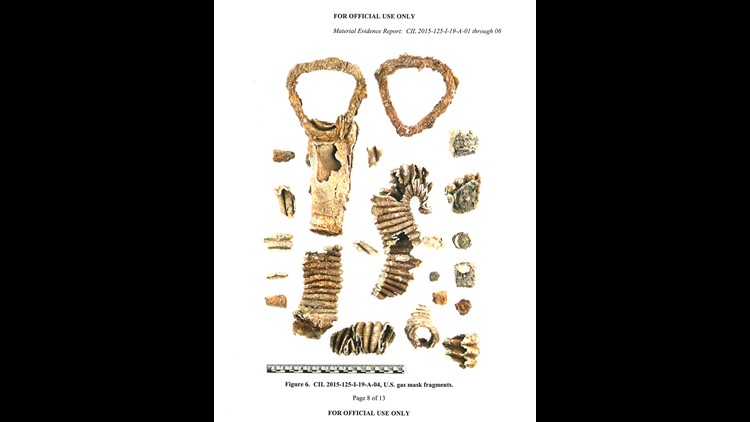

His skull is still inside his helmet, a gas mask and goggles disappearing into the dark sand. A silver canteen comes into view, along with rib cage fragments and pieces of poncho underneath his leg bones.

He is an unidentified Marine, found underneath a house, in the middle of a Tarawa shantytown.

“The first time I saw it, I just stared at it for a while,” said John Weatherell, one of the Americans taking part in the excavation efforts. “And my God, you know, what it was like to come into this fire. And this is where you’ve been. You lost 75 years of your life, right here.”

Weatherell is one of the members of History Flight, a non-profit charity now awarded government contracts to excavate on the island. He is 81 years old, a retired Army staff sergeant whose mentors fought on Tarawa.

“My dad was gone, so I looked to them as a kid,” he said. “I think about my sergeant here, how one of them fought hand-to hand, how he was lucky to have made it.”

Washington, D.C. native Mark Noah founded History Flight 14 years ago. His work made him an honorary Marine, after his team found Brisbane and returned more than 100 Marines on Tarawa to America.

“You can’t find what you’re looking for unless you’re standing on top of it,” Noah said in an interview. “With every individual that we bring back to America, we’re bringing people back here from another era. We’re helping restore their dignity. We’re giving closure to their families.”

Noah is a commercial pilot who relied on donors and his own money to fund History Flight, bringing cadaver dogs and ground-penetrating radar to a working Tarawa seaport in 2015.

Noah and a team of historians overlaid archival maps with current images from Google Earth, narrowing the location of Brisbane’s cemetery to a gravel parking lot.

Their excavation on the site proved successful, recovering Brisbane’s nearly complete skeleton. The find was part of the largest recovery of missing in action troops in U.S. history.

PHOTOS: Excavating WWII servicemembers on Tarawa

History Flight provided WUSA9 access to the site where Brisbane was found, in addition to an active excavation area within one of the island’s sprawling neighborhoods. Three days after WUSA9 embedded with the anthropologists, Brisbane’s niece and nephews gathered at Arlington National Cemetery to welcome him home.

They were unaware on the day of his American re-internment, June 9, 2017, that his remains were previously unmarked, found below grime and gravel, truck traffic and cargo.

“Nobody said anything about a parking lot until you said it,” remarked Brisbane’s niece, Judy Landry.

Family bewilderment devolved into a sense of betrayal.

“It’s deplorable,” she exclaimed after viewing video of squalor near the Tarawa graves. “The difference between where they’re buried [on Tarawa] and where my uncle was just buried [in Arlington], it’s atrocious. They should be brought home like every other serviceman that gave their life in this war or any war.”

But building within Brisbane’s nephew, John Bloemer, was a sense of anger. Bloemer sat next to his sister Judy, parsing through paragraphs, papers and photos revealing the reality of the island.

His voice quivered, statements made to the point of shouting, realizing no one knew or marked where his uncle rested for two generations.

“There was a memorial that’s now gone? Somebody went to the trouble to cast something in bronze and put a big cross, and the cemetery’s gone?” Bloemer cried in disbelief. “I mean, that part is just, that I found out all this today!”

“People need to know about this because 73 years ago, we were in a real fight,” Bloemer continued.

“And now, they’re still there? We left these guys behind? The Marines? We left Marines behind! It’s unbelievable. It’s unbelievable. To see this.”

Work ahead, as funding fell

The Defense POW / MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) is the arm of the Pentagon charged with the daunting task of recovering and identifying as many of America’s missing service members as possible.

In a wide-ranging interview, Col. Fern Sumpter Winbush, the acting director of DPAA when the agency became fully functional in January 2016, said her personnel are not taking their eyes off Tarawa.

She was asked to react to the Brisbane Family learning the full circumstances of their uncle’s Pacific burial.

“No reaction,” Sumpter Winbush began. “The only thing I have to say to that is, where we have found remains, again in many cases, 70 plus years later, a lot has happened.”

Asked whether families in the future should know about what happened before repatriation, Sumpter Winbush agreed.

“Sure, sure!” she said. “And I can’t tell you why they weren’t told that it was a parking lot. Hopefully in the future.”

The Defense Department established DPAA in January 2015, after decades of mismanaged MIA recovery efforts. Two departments were fused into one, after government teams on average identified only 72 missing service members each year. In 2016, the total number rose to 168.

But a review of records shows when Congress demanded DPAA identify at least 200 missing Americans beginning in fiscal year 2015, DPAA funding fell millions of dollars.

DPAA started with a budget of $127.4 million in fiscal year 2015, but funding fell to $112.7 million by fiscal year 2017.

“$112 million, that’s not, acceptable,” Sumpter Winbush said. “What I think what the perfect baseline is right now with regards to funding, is about $130 million.”

Dollars directed towards DPAA began to decline in part because of the arcane nature of the Pentagon’s budget process. The agency was established in the middle of a five-year budget cycle, making it difficult to request additional funds. Sequestration also contributed to a downturn in spending.

As a result, recovery missions were canceled.

Non-profits like History Flight began to fill the void.

“We took a dip of about 35 percent of our operations, we had to cut,” Sumpter Winbush said. “That was just the reality.”

After Mark Noah of History Flight financed the recovery mission to find Brisbane’s grave, DPAA reimbursed the non-profit for the excavation effort. Noah continued to use his own money to begin one of this year’s excavations, requesting reimbursement from the government.

But Noah and his team said the government contracts and funding they need to finish their work, simply do not exist. Retired Army Sgt. John Frye, History Flight’s team leader on Tarawa, escorted WUSA9 through three sites among the island communities, where scores of unexcavated remains are believed to be in danger.

“[The islanders] dig wells, they dig trash pits, you know, they’re constantly digging in their own yards,” Frye said in an interview. “And many times they will turn up human remains, and they don’t tell anyone. They just re-bury them in a rice bag or something. Or sometimes they just take them out in the lagoon and dispose of them.”

In 2014, Frye and his team were able to locate three original burial trenches in one neighborhood alone, recovering military artifacts as well as arms, legs, hands, feet and bone fragments. History Flight returned those remains to DPAA. Scientists then analyzed the samples at a Defense Department lab.

The bones were eventually buried in Hawaii’s National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific.

A full excavation at the site has never taken place.

“Everyone in America likes to look at the black POW / MIA flag that flies over the statehouse or the post office, and they say, ‘Oh yeah that’s a great thing, let’s support the troops,’ But where’s the backup?” Noah asked.

“When do they support what they’re saying, because they don’t. And the simple fact is, DPAA is totally underfunded for the size of the mission that’s at hand, and it’s America’s fault. It’s a disgrace.”

A watchdog adds concerns

In July 2013, one of the nation’s top watchdogs with the Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a scathing report, calling for an upheaval of American efforts to return its war dead.

Brenda Farrell, director of defense capabilities and management issues at GAO, sent out nine recommendations to the Pentagon – first and foremost, a suggestion to merge disparate factions into the single agency that would become DPAA.

In the beginning of WUSA9’s review of government records in March 2017, three out of nine recommendations were fully implemented.

By November 2017, seven are now in effect.

But in an interview, Farrell said while there is optimism, the risk of DPAA digressing is still great, and critical goals remain elusive.

“It’s been seven years since Congress stepped in and put their mandate to meet a goal of 200 identifications per year, by fiscal year 2015,” Farrell said. “So I’m disappointed that they didn’t move faster of course, to meet that goal in 2015. But the good news is that they do have a lot underway.”

The two remaining recommendations yet to be implemented endanger the prospect of faster identifications. The highest priority issue – personnel files do not exist for all American MIA service members.

“This is one that they’re struggling with the most, Farrell said. “They do have files for those from the Vietnam era, but it’s expanding it to Americans missing from World War II that’s an overwhelming work load for them.”

GAO projects DPAA could have an efficient working file system in two years. The effort will now likely be expedited, after funding for DPAA was increased to $131.2 million for fiscal year 2018.

“The challenge that we have is taking, in many cases, hard files, flat files, pieces of paper, photographs, negatives, microfiche, and getting them into that new system,” Sumpter Winbush of DPAA said. “And oh by the way, some of that information, is still classified.”

GAO also lacks confidence that two labs assigned to examine artifacts from excavation sites operate in a way that does not duplicate work. Farrell said the labs lack clear standard operating procedures, potentially backlogging efforts as families wait for cases to be closed.

“If those two labs aren’t communicating well with each other, then who is passing along the information to those who keep family members apprised of the status of their missing person?” Farrell said.

“It also can slow the process down if it’s not clear which lab is doing what. It’s, ‘why do you want two labs doing the same thing?’”

We’ll meet again

But a world away from Washington, the anthropologists who recovered Brisbane continue working in the shadow of colossal Japanese cannons. The artillery awaits an armada that has come and gone, as Americans walk among the wreckage.

In History Flight’s building near Brisbane’s grave, at least two skeletons at a time await both analysis, and a military C-130 cargo plane to take them home.

When a quiet falls over the concrete lab, there is little left to say.

In those moments, the Americans remember what the men would’ve heard as they sailed towards Tarawa. A modern iPod speaker sounds more like a phonograph, as it plays the 1939 war ballad, “We’ll Meet Again.”

So will you please say hello,

To the folks that I know,

Tell them I won't be long,

They'll be happy to know that as you saw me go

I was singing this song.

We'll meet again,

Don't know where, don't know when,

But I know we'll meet again, some sunny day.

It’s a reminder of the promise they keep, to never leave a man behind.

“There are deep family wounds from this war, and from this battle in particular,” said anthropologist Hillary Parsons. “There are scars that never healed, and that transcend through generations... We feel that with this music.”

The stories of the fallen now reemerge because of the men and women who followed them to the far reaches of the Pacific – this time, with shovels and brushes.

“Welcome home, my Uncle Howard,” said John Bloemer, Howard Brisbane’s nephew.

“For them to go out in the middle of nowhere and dig up our uncles, fathers and brothers, we all owe them our gratitude, for fulfilling that forgotten promise.”