NORFOLK, Va. — There's a name that means power to Dunnsville, Virginia man Ronnie Sidney II: Lewis Corbin.

Corbin was Sidney's third great-grandfather. He escaped slavery from the Bellevue Plantation in Essex County in the 1800s and fought in the U.S. Navy for the Union in the Civil War. Meanwhile, the son of his enslaver, Robert Ware, fought for the Confederacy.

"My dad told me about Lewis Corbin's story... so now I have a personal connection to history," Sidney said.

Corbin's story set Sidney on a path to make changes in his own life: "I said, 'How can I complain when I had ancestors who endured slavery?'"

The social worker and motivational speaker launched a series of children's books not only to honor his family history but to highlight the personal hurdles he has overcome.

"I wanted to write the book I wish I would have had when I was young," Sidney explained while cradling Nelson Beats the Odds. He recalled graduating from high school with a 1.8 grade point average and was made to believe he had a learning disability.

Now, the dean's list college graduate is a best-selling author.

He's working to live up to Corbin's legacy.

"He escaped slavery and then went to the Hampton Roads area to join the Navy and to come back to the same community he was born in and fight... just showed you how much he wanted freedom for his family. It just made everything that I was going through minimal because his man did so much."

The Ware family is still well known in Essex County with many descendants of the original owners of Bellevue still residing in the area.

That includes Hannah Tiffany Overton. She and Sidney have formed a special friendship. They met at a Black Lives Matter march around the time Sidney led the charge to remove the Confederate monument from the public square in downtown Tappahannock in 2020.

"She fought with me to help remove the monument," said Sidney.

It was a fight Overton was willing to take on. "It didn't feel right with it located between the General District Court and the Circuit Court, and its prominent spot in the middle of town," she said. "It felt intentional, which it was. If you read about the Jim Crow era, you know that it was put there intentionally."

Her ancestor's name, Robert Ware, is etched on the base of the monument.

Unfortunately, for many African Americans precious ancestral stories are never revealed to empower future generations.

"If you have those enslaved ancestors, as most folks who identify as African Americans -- whose families have been here for awhile -- what is known is that we were not treated as people. We were treated as possessions," explained Bessida Cauthorne-White, president of the Middle Peninsula African-American Genealogical and Historical Society.

The names of the enslaved were not listed in many historical documents. 1870 was the first time formerly enslaved African Americans were named on the federal census.

Unearthing the family roots is challenging but many groups are up to the task. Today, at least 19 states have chapters of the Afro-American Historical Genealogical Society (AAHGS).

For 30 years, Newport News genealogist and genealogy educator Renate Yarborough Sanders has combed through thousands of documents connecting the dots between back then and now.

"1870, where people refer to it as this brick wall. Instead of seeing it as this brick wall, I see it as the place where we can determine which road we go down with our research. Are we looking for someone who was likely enslaved or are we looking for someone who we have found to be a free person of color?"

The challenge is to find the names that can lead a person today to answers about their enslaved ancestors. Slavery was a form of identity theft.

"Names are one of the biggest areas of challenge. For instance, we may only know the first name or we may find that ancestor with a specific last name right after emancipation, and then we don't find them again," Yarborough Sanders said.

Newly emancipated slaves did not always assume the surname of their last enslaver. Some took the opportunity to name themselves after something or someone more meaningful.

"They could take the name of their occupation like Carpenter, Shoemaker, or of a famous person that they admired like Lincoln or Washington or Jefferson. And we find a lot of Black families with those last names," Yarborough Sanders explained.

10 Million Names

Imagine one database into which a person could tap and find the names and stories of some 10 million enslaved people of African descent in pre- and post-colonial America.

That's the ambitious goal of Boston-based American Ancestors' 10 Million Names project.

Tufts University's Director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy, Dr. Kendra Field, is the chief historian of 10 Million Names.

"As a historian, I come across the names of formerly enslaved people every day in the course of my research. But even for me, I never quite imagined there could be one place where all this information would live together: one database that might be searchable," Field said.

A team of historians and genealogists will collaborate with researchers, families, and data partners across the country to catalog this documented history that will live in an online database for anyone to access for free.

"So it's really a way to say that African American people were people. And they had names. They were called something. So, we're trying as best we can to restore those names so that people can find their ancestors," said Dr. Kerri Greenidge, a member of the 10 Million Names Scholars' Council.

On the 10 Million Names website, individuals are invited to submit their family research. It's also a hub for African American genealogy resources.

Research newcomers will find instructions on getting started, with organizational tools, family charts, and research templates.

The Roach Family

Genealogy research has been of great interest in my own family. Many people may not know, but both my maiden and my married name are "Roach." I married Harold Roach.

The family elders assured us we were not related. He grew up in Virginia. I grew up in North Carolina.

During the COVID pandemic, Harold began researching the Roach name. Our DNA submissions to Ancestry.com show we are not a match but as we would learn, that doesn't mean there's no connection.

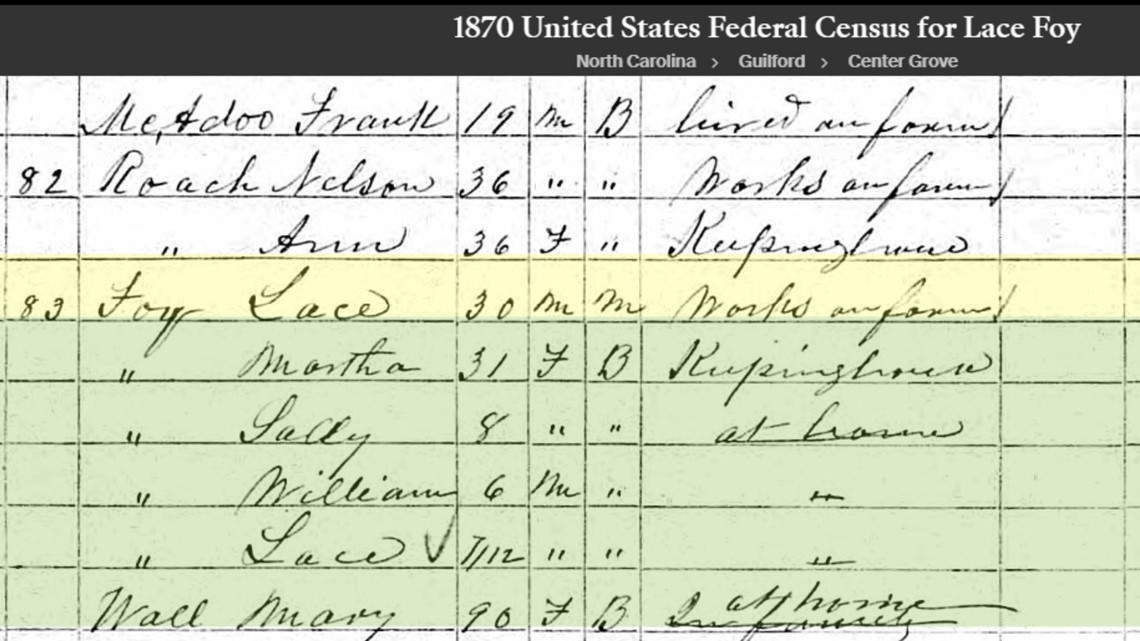

In 1865, my second great-grandmother, Ann Harris, married Nelson Roach in Guilford County, NC. She became Ann Roach. In 1875, she gave birth to James Roach. But when he got married decades later to Keturah Burks, he did not list Nelson Roach as his father on his marriage license, but Lace Foy.

That's how I found out that Lace Foy was actually my second great-grandfather. On the 1870 census, he's listed as a neighbor of Ann and Nelson Roach.

That discovery sent Harold on a determined search to find out more about Foy. He discovered a Division of Slaves document in the Rockingham County, NC Slave Deed Index. And like locating a needle in a haystack, Harold found the name "Lace" as enslaved by Benjamin Webster in 1860.

Upon Webster's death, Lace was bequeathed to Dr. B. F. Foy, more than likely how Lace got the Foy name.

Our discoveries didn't end there. Lace is listed as a "mulatto" on the 1870 census, meaning he was biracial. That prompted me to search my DNA matches on Ancestry.com for any connections to Webster, Lace's former enslaver.

Sure enough, a match showed up as a potential 3rd or 4th cousin. And on this cousin's family tree were relatives of Benjamin Webster, evidence that he is possibly my third great-grandfather.

There was yet another amazing revelation for Harold and me. We both then wondered who was Nelson Roach, the man I thought was my second great-grandfather. He was married to my second great-grandmother, Ann.

It turns out, he's related to Harold.

Harold's research had led him to the same areas of North Carolina: Guilford and Rockingham Counties. His family line met up with a woman named Sarah Roach, who he believes is his third or fourth great-grandmother. Nelson is her son.

He petitioned the Freedmen's Bureau in 1867 to have his two nieces, Lora and Millie, removed as indentures from their former enslaver, Thomas Roach.

"I guess evidently, he was trying to maintain control over these little girls after slavery ended," Harold said.

A move that was not unusual as former enslavers often abused apprenticeship laws to hold on to the value of their labor.

"African Americans' parents who had been enslaved -- between 1865 and 1867 in North Carolina -- were incredibly vulnerable to the fact that a slave owner could essentially use this law and say, 'You don't control or dictate where your child is, I do as their former slave owner,'" Field said.

Nelson Roach won his fight after his nieces showed up to the Freedmen's Bureau office "raggedy and dirty" and clearly disputing claims by Thomas Roach that they were "perfectly satisfied" with "no complaint of ill-treatment."

"Eventually, the truth was discovered because the little girls were not being cared for, not being educated. It took the Freedmen's Bureau to make that discovery and cancel those indentures," added Harold.

Nelson's resilience and fortitude to fight for his own is a proud discovery for our family.

The First Africans

Names mean everything to the Hampton, Virginia's Tucker family. They are widely believed to be descendants of two of the first enslaved Africans to English North America.

Anthony and Isabella were two of the documented "20 and Odd" Africans forced to present-day Hampton in 1619 on the English ship, the White Lion. The couple lived on the farm owned by Captain William Tucker in Hampton and they gave birth to a son, William, who is believed to be the first documented African born in America.

Today, the Tuckers honor their ancestors each year with a ceremony in the cemetery that bears their name in Hampton's historic Aberdeen Gardens community.

"It means that they were somebody and not just a number that was documented or just 'Negro boy' or 'Negro girl.' They are somebody. We can identify them as a person," said Wanda Tucker, one of the family historians.

Someday, they hope ground penetrating radar can verify if Anthony and Isabella are buried there.

"There's that possibility. Not only do we know the names of our ancestors but we can possibly know where they have rested," added Tucker.

About 30 miles from Hampton, the name Angela is celebrated at Historic Jamestowne. She was forced to English North America on board the British vessel The Treasurer, also in 1619.

Listed on the 1625 muster as "Angelo," she lived and worked in the home of Captain William Pierce.

Historians and archaeologists at Jamestown have worked to elevate Angela's voice. In recent years, archaeological remnants of the Pierce property have been recovered.

"It's the quiet spaces in history where we become American. So for Angela to enter into a household, she's changing food ways, she's changing medicine... practices from Africa, " said David Givens, Jamestown Rediscovery's director of archaeology.

Living History

Elusive documentation of the enslaved made oral history all the more important in the African American community. The best records in history came from the people who lived it.

In the Dobbins family, the patriarch Harold is 101 years old. Not looking a day over 80, Dobbins and four generations of his family gather in Hampton to celebrate his birthday.

His memories of joining the Navy and fighting in World War II are ones he proudly shares.

"I’ve been in three wars, three conflicts. I'm not supposed to be here anyway. God saved me," he recalled. "The Dorothea Dix [a WWII ship that Dobbins served aboard]... that plane dropped that bomb and missed that ship, I don't how he missed that ship, that big ship! Had to be God."

Some day the youngest of this group will tell that story.